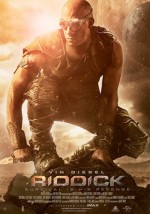

Riddick

Vin Diesel and David Twohy‘s Riddick sees the filmmakers and their creation on a search to return the anti-hero to his roots after the operatic excess of his last outing and, despite a few pitfalls along the way, they largely succeed.

It’s been nearly a decade since their last “Riddick” film, the ambitious but ill-received Chronicles of Riddick; long enough for studios and audiences alike to forgive its missteps and re-embrace Diesel’s most interesting character. But if they’ve forgiven, they certainly haven’t forgotten, a lesson Diesel and Twohy have taken to heart as they try to meld together the expanded mythology of the character from Chronicles with the elements that drew filmgoers to him in the first place.

Left reigning at the end of the last film as the leader of a death cult bent on universal domination, Riddick (Diesel) and his creators have realized this might not be the best milieu for the mass murderer-with-an-honor-code-of-gold who, worried himself about getting too soft and “civilized” by said death cult, decides to go on a quest for his legendary home world: Furya.

It’s the logical move both from the point of view of Riddick and that of anyone who lived through Chronicles initially chilly reception: get Riddick away from the non-intrinsic elements introduced there without ignoring them or treating them as if they never happened. That has included returning the franchise to its R-rated roots and the grittiness it needs to thrive, even if it does lead to an overabundance of onscreen machismo which threatens to infect the viewer, and some of the actors, with terminal testosterone poisoning from time to time. Still, it’s the kind of environment a character like Riddick needs to thrive in, a fact both filmmakers and character are in complete synch on.

Riddick himself might not agree with that, at least at first. Instead of being led back to Furya, he is betrayed and left for dead on a savage planet where he must become the man he was, and the filmmakers must rediscover what makes him tick, in a nearly silent sequence broken up only by Diesel’s sparse narration. It’s one of the few beats in Riddick which doesn’t reference past iterations of the franchise, and as such it is by far the strongest section of the film, as Riddick fights off wild alien dogs, sets his own broken leg, and discovers the strange scorpion creatures that sit atop the local food chain (as long as the food chain remains near water, since they can’t leave it).

Twohy effectively and efficiently lays out the geography and dangers of the new planet, providing us most of the information we’re going to need to get us through to the end in the kind of show-don’t-tell filmmaking Hollywood frequently preaches but never follows. It’s the kind of invention the lack-of-studio-money leanness requires from Riddick, which also requires the film to remain in one location with a small cast.

It doesn’t stop Twohy from wallowing in some clichés, however, like the training of a local non-domesticated alien wolf pup into a faithful pet. It helps that a hefty portion of his crew are “Riddick” veterans; Pitch Black cinematographer David Eggby and his crew have created a world that fits seamlessly with both of the prior Riddick films, though the lower budget does occasionally show itself during larger effects sequences.

Eventually, though, everyone realizes Riddick can’t spend an entire film alone with his dog, which means — in the “Riddick” universe, anyway — some bounty hunters have to show up to try and claim the reward on him. Rather than have the film turn into a rote action piece, Twohy uses it as an excuse to turn up the tension, as Riddick (after monopolizing so much of the beginning) disappears to make room for the mercenaries who show up.

For a film built so much on the shoulders of one person, it’s an incredible risk to suddenly push him aside, but in Twohy’s hands, it becomes a method for expounding on Riddick’s nature, allowing him to torment the bounty hunters with the Batman-like feats of stalking (in broad daylight, no less!) he is legendary for and which absolutely would not work if shown on-screen. It brings home the feel Twohy — who has co-written and directed every “Riddick” film — has not just for the character but for the cinematic world they inhabit, including how far to push the rules of that world.

Which isn’t to say Twohy is above referencing the more fondly-remembered portions of the franchise; he just prefers to make like Bach’s Goldberg Variations, twisting the familiar into ever-so-slightly newer shapes. Nearly simultaneous with the disappearance of Riddick, here we’re introduced to a group of rival mercenaries who’ve also come for the bounty, including one (Matt Nable) with a familiar name and a very old grudge against Riddick. While the first group, led by the craven Santana (Jordi Mollà), is the motley sort we’ve come to expect from the franchise, this group is more put together spit and polish, and much of the middle of the film is driven by the competing personalities, especially once Riddick starts putting the screws to them.

Not that there isn’t enough pressure on them already, due at least in part to Boss Johns‘ group bringing along Dahl (Katee Sackhoff) as the only woman on a planet at the moment populated by the most alpha of alpha males. Her presence allows Twohy the opportunity to take a break from his action-thriller to comment on the over-masculinization of his film, which is all about hard men doing hard things to each other. He doesn’t seem to want to take that opportunity, relishing only the “badass” elements of character, fetishizing it in everyone over and over; even Dahl herself can only compete in this world of men by being the manliest.

Ironically, no one seems that comfortable with getting too far away from the familiar and into the dark, and for all the play Riddick does, eventually the survivors must band together against the water-logged predators free to roam the wilderness and eat whatever they come across when the rains come. For all of its early inventiveness, Riddick eventually succumbs to its need to win back its fan base, more and more resembling the Pitch Black clone the series has been trying to avoid ever since a sequel was green-lit.

Twohy is still playing variations, of course, as he once again casts Riddick into the dark, fighting for his life against monsters with a man named Johns, suggesting the point of the film is to view how much Riddick has changed from then to now. Riddick, by need and by design, seems immune to change — except for the slow variety, the kind that affects glaciers and landmasses — and becomes noticeably less interesting when his internal alchemy is tampered with.

He’s still entertaining to watch when he does what he does, and at its best Riddick is a fun reminder of what made Diesel a star to begin with, especially when he doesn’t have to pull his punches. But the filmmakers also bump their heads against the ceiling of their setup once more, and will soon have to start thinking truly dangerous thoughts again: putting Riddick back into the kind of story he hasn’t done before.

I’m thinking a nice romantic comedy.

Cast: Vin Diesel as Riddick; Jordi Mollà as Santana; Matt Nable as Boss Johns; Katee Sackhoff as Dahl; Dave Bautista as Diaz; Bokeem Woodbine as Moss; Raoul Trujillo as Lockspur; Conrad Pla as Vargas; Danny Blanco Hall as Falco; Noah Danby as Nunez; Neil Napier as Rubio; Nolan Gerard Funk as Luna; Karl Urban as Vaako.

Leave a Reply